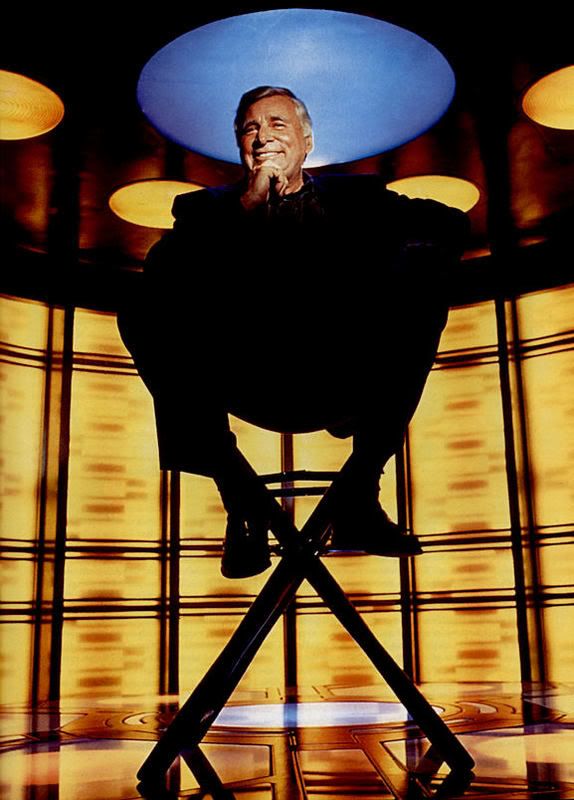

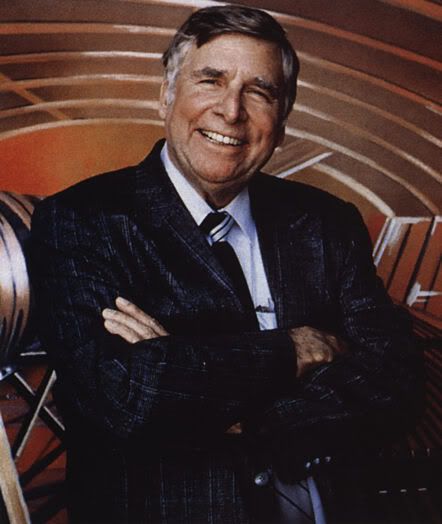

David Gerrold began his professional career as a writer in 1967 with "The Trouble with Tribbles," one of the most beloved and popular episodes of the Star Trek franchise. Since those early days with Trek, he has published more than forty books, including The Man Who Folded Himself, When HARLIE Was One, and the many books in The War Against The Chtorr and the Dingilliad series. After being nominated repeatedly throughout his career, he won the Hugo and Nebula in 1995 for The Martian Child, an autobiographical story about his son's adoption.

Having written episodes for over a dozen different television series, including Star Trek, Star Trek: The Animated Series, The Twilight Zone, and Babylon 5, while simultaneously establishing himself as a master in the genre of science fiction literature, Gerrold has become an authority on science fiction writing, as well as Star Trek.

In fact, many of his critical insights on Trek, first published in his 1973 The World of Star Trek, were directly incorporated into the writer's "Bible" of Star Trek: The Next Generation, which is not surprising considering Gerrold wrote the first draft while working closely with Roddenberry and others. Over a decade before TNG premiered, Gerrold brainstormed a Klingon and counselor on the bridge, families on the Enterprise, and the role of the first officer in leading away teams to planetary surfaces, among other notable ideas that defined TNG as different from TOS.

Arguably, David Gerrold deserved the title of "co-creator." Yet, after a fall-out with Gene Roddenberry during the first season, his Trek legacy has been whitewashed, particularly by official Paramount entities, like startrek.com (which does not credit Gerrold as part of TNG's creative staff) and especially by David Alexander's "authorized" biography of Gene Roddenberry, a book that paints a very unflattering and unfair portrait of Gerrold.

With his consent, we at Trekdom are posting a letter that Gerrold wrote to David Alexander in 1994. Not only does this letter clear the air about his experiences during that chaotic and hurtful first season of TNG, but it also demonstrates that Roddenberry's "official" biography is neither objective nor accurate.

We present this letter so that Gerrold's contributions to Star Trek will elicit further celebration, while also demonstrating how his predictions have proven correct.

-----------------------------

Dear Mr. Alexander,

For nearly seven years I refused all requests for interviews about my association with ST:TNG and the problems that the staff had with Gene Roddenberry. I refused to talk to Joel Engel for nearly six months, and only changed my mind AFTER several close friends urged me to do so to put closure on this whole business.

I began by giving Joel Engel copies of all the memos from the first seven months of ST:TNG. I waited to see what his reaction would be. After he read the memos, he came back to me with questions. The first question he asked was,"What did Gene write?" In the first seven months of the show, Gene wrote one 16-page draft of the bible, and less than a dozen memos, several of which were embarrassing for their sexual content.

As I have said elsewhere, I was Gene and Majel's friend for over twenty years. I taught Gene how to use his first computer. I remained loyal to him when others had abandoned him, I remained loyal when there was nothing to gain, when too many others considered him a has-been -- I remained loyal to Gene because I cared about him.

My problems on the show were not with Gene as much as they were with his lawyer who consistently violated WGAW rules in Gene's name. The lawyer also convinced Gene that he couldn't trust any of his old friends including me, DCF, Bob Justman, and others; thereby isolating him from information that might have helped the show. Remember, I WAS THERE. I saw what happened. Your star witness, as you yourself have acknowledged, was losing his facilities. And as many have noticed, Gene's grasp on truth was slipshod at best...

Most of us on staff knew there was something wrong with Gene. Most of us loved him enough that we were desperately trying to find ways to make sure that he could do his best; but when the lawyer declared war on the staff, he turned the place into an armed camp. I quit rather than participate.

I never sued Gene. The Guild brought an arbitration on my behalf against Paramount for wages owed. Gene took it personally, because the lawyer told him it was a personal attack. It was not. I admit to some anger at the lawyer, and at Gene for allowing the situation to happen; but I also had direct evidence-- Gene lied to my face, and then asked Herb Wright to cover for him -- that Gene had lost touch with his affection for his old friends. Even after I left, I was hesitant to speak to the Guild. It was only when two people on the Star Trek staff started telling people (erroneously) that I had been fired that my agent asked me what I had done on the show. I showed him the stack of work I had written, including the *first* Writer's/Director's Guide, and he sent the material over to the Guild.

My agent made the claim for co-creator credit, not me. And he did so without my knowledge. The Guild looked over the matter and said that Gene's rights to the created by credit were protected because the show was a spinoff of Star Trek. I never argued with that because I never wanted to take anything away from Gene. I only wanted to be fairly paid for writing the bible and doing additional producer-level work.

What Gene obviously did not tell you was that on the day he brought me on staff he told me that he believed I understood the nature of Star Trek better than anyone else in the world, perhaps even better than he did. He said I would be his Creative Consultant and later, a producer. He said I would attend every meeting and make sure his wishes were met throughout the staff. During those first few weeks, I helped bring aboard Andy Probert who designed the ship, wrote a memo suggesting Wil Wheaton for the character of Wesley, created the character of Geordi LaForge (including his name), and other aspects of the show.

BTW, Gene read every Starlog column before it was turned in, and signed off on every one. When I asked him what title I should use, he said, "Head Writer."

When the lawyer came aboard, he began restricting my authority and my title, and even denied me a parking place on the lot. At that point, Gene's relationship with all the staff members began to deteriorate because the lawyer became Gene Roddenbarry's Iago.

After I left the show, for seven years, I had to listen to Star Trek "loyalists" tell stories about me that weren't true and that were obviously designed to hurt me personally as well as hurt my career. One individual told conventions not to bring me in as a guest. Another was telling people that I was mentally ill. A third loyalist destroyed a book deal for me at Pocket Books. And so on. The characterization was created that I was going around badmouthing Trek and Gene, when in fact, I was trying very hard to get on with my life as a novelist. It was difficult to refute the charges when Gene had access to 10,000 people at a time and I was saying "no comment" so the lies about me began to take on a terrible life of their own.

FYI, facts that you failed to mention in your book: I've written over thirty books, at least that many TV scripts, and story-edited three TV series. I created Land of the Lost for Sid & Marty Krofft, and have done episodes for Logan's Run, Twilight Zone, Babylon 5, Star Trek, Star Trek Animated, and other series. I've written Writer/Director's Guides for six series, three of which have been produced. I've written nearly a hundred short stories and nearly a thousand columns and articles. Your book seemed to indicate that I had no other career than Star Trek, when in fact my novels routinely make the Locus and B. Dalton Best-seller list. Again, your research was either flawed, or you deliberately withheld information.

During the summer of 1992, in preparation for the adoption of my son, I did a course in personal effectiveness, and one of the exercises was about forgiveness. Forgiveness was defined as "giving up the right to resent you in the future for events that happened in the past." After considerable soul searching, I wrote a note to Gene, which you referred to in your book. It seemed to me that by that act, I could finally put Star Trek behind me once and for all and focus on the real joys in my life, my writing and my son. Plus, I knew that Gene's health was failing, and it seemed like a good idea to give him some measure of peace before he died. It was a way of acknowledging the good times and thanking him again for them. It was a difficult note to write because I knew that it would be misinterpreted by those who insisted on seeing me as a villain.

(BTW, perhaps Richard Arnold didn't tell you about the times he came into Gene's office and found him weeping at his desk that "all his friends had left him" and he didn't know why. So even Gene was aware that something awful was happening around him.)

Your discussion of The Trouble With Tribbles is inaccurate. Robert and Ginny Heinlein were friends of mine from 1971 until the time of his death. After Ginny gave up the house, she entrusted me with Robert's cat, Pixel, because she couldn't keep him anymore. If Ginny regarded me as anything less than a friend, do you think she would have trusted me with one of the most famous cats in SF literature?

Your reportage of the matter of the Guild arbitration is also erroneous. It was to Gene's advantage to downplay the settlement because it made my claim look frivolous, but in point of fact, there were over twenty witnesses prepared to testify against Gene and his lawyer's behavior. After the testimony of the first five was fully heard, Paramount's lawyers began stalling the hearings. What we were told (unofficially) was that Paramount saw the validity of the claim and wanted to settle it, but that Gene's lawyer had turned it into a grudge match.

At that point, the Executive Director of the WGAW had a private meeting with Gene Roddenberry in which he explained several very good reasons why Gene should encourage a settlement. Not the least of these reasons was that Gene's own reputation would be sullied if the testimony continued. A settlement was made shortly thereafter.

What I find most amazing, however is your bald-faced assertion: "It was Gerrold's choice with Engel to open that old matter, thinking that there was a confidentiality agreement in place...."

The terms of the agreement with Paramount were that I would not discuss the terms of the *settlement. There was nothing in the agreement to prohibit me from talking about the *causes* of the grievance. That I withheld public discussion of Gene's failings for so long was partly out of respect for Star Trek and my affection for the show and its fans, and partly because there was so much more happening in my life of much more importance.

In actual fact, it is you who violated the terms of that confidentiality agreement in place by appearing to discuss the monetary terms of the settlement in your book. The numbers you quoted were not even equal to my income tax refund for that fiscal year. That's as much as I can say without breaching the confidentiality agreement.

I do find it outrageous that you claim you were given the information you were given by a studio attorney, because that puts the studio in the position of knowingly violating their own confidentiality agreement. The WGAW will be very interested in that fact. Thanks. Whoever the attorney was, he lied to you about the facts. Unfortunately, I cannot give the correct information without violating the part of the confidentiality agreement that is in effect. The dilemma here is that others are free to lie about me. I am prohibited from refuting those lies with the documentation.

Even more disingenuous, is your justification that because I spoke to Joel Engel, you were free to hash out the matter in your book. Because your book was published near-simultaneous with Engel's, you had no idea what I might or might not have said to Joel Engel. Therefore you had to have been planning your scurrilous assault on my reputation from the git-go. Indeed, I have it on the authority of someone who is in a position to know that you were given specific instructions to portray me as Gene's enemy. It was only after I was informed of this information that I agreed to speak candidly with Joel Engel.

Now I do want to talk about Gene. Many people have said a lot of things about him. I knew him better than most. I'm certain that I knew him better than you ever did. I saw him at his best and his worst. I saw him stand up to a studio exec about an issue of unconscious racism. But I also heard him say sexist and stupid things about women in general and Majel in specific. I heard him make inspiring speeches about challenging writers to tell the best stories they could, but I also heard him rage against good people who he felt had betrayed him. The day we moved into our offices he said, "I'm going to lose a lot of friends before this is over." (I should have taken that as a warning.) I knew him when his mind was so sharp he could cut a seven page scene down into four lines of dialogue. And I knew him when he was so fuzzy that he couldn't remember how a scene had begun when he got to the end of it.

At his best, Gene could inspire people to be better than they believed they were capable of. That was his greatest virtue. He was a man who could sell ice to penguins.

His greatest failing was that he didn't fully believe in his own vision himself. Once he'd inspired people, he couldn't trust them; perhaps because on some level he was so insecure about his own beliefs, or perhaps because he thought people had fallen for his vision too easily, he never believed that they were as deeply enrolled or as deeply committed as they were.

People believed in Gene and in Star Trek. Nobody believed in him and the show as much as Dorothy and myself. We have our careers as demonstration of that. But Gene never allowed himself to believe that anyone was in it for anything but the money and the glory, and he was unwilling to share the credit. As a result, he was a terrible manager. He hurt people, he betrayed them, he left a trail of broken promises. And he always made sure he had someone to blame when things went wrong. NBC. Harlan Ellison. The studio. Harve Bennett. Robert Wise. And finally me. If it hadn't been me, it would have been someone else.

Gene was like the blind man with the lantern. He lit the path for many others, but he flailed in darkness himself.

I do not believe that you understand what Star Trek really meant to many of us who worked on the show. It was a wonderful dream for Dorothy and myself and almost every writer who came in. In our eyes, it was the best TV show in the world.

We worked as hard as we could. We wanted to make Gene happy. We wanted to make him look good. And then we were told that our work was sh!t and we had to do it over again. So we did. Again and again and again. Then the weird stuff got weirder. Credit-grabbing. Lying. Unjustified temper tantrums and bawlings-out. Vilification. Lies to us about how the studio hated us. Lies to the studio about how we were disloyal. We were getting so much conflicting information, we had no idea what was going on.

Eventually, I was approached privately by a major studio exec who asked me what was going on. I didn't want to be disloyal to Gene. I tried to beg off. He promised me confidentiality. He told me that the studio was thinking of pulling Gene off the show. I said that would kill him. Even in the midst of it, I was still trying to be loyal to Gene, thinking that he was still loyal to his staff. At another point, even Majel asked me if everything was all right. I was afraid to tell her the truth because I didn't want to hurt her feelings. (I have always had a great deal of affection for Majel, for reasons I won't discuss here.)

When I finally realized just how sick Gene was -- and just how unworkable Star Trek had become -- I became physically ill. From March until shortly after I quit, I was seeing one doctor after another trying to find out why I hurt allover, why I had no energy, why I couldn't eat. I was diagnosed as hypoglycemic, suffering from Epstein-Barre, and was going to be tested for other neurological conditions as well. I left the show in June, and started working on Trackers at Columbia and by the end of August most of my symptoms had disappeared. The therapist's conclusions were that I had been under terrible emotional stress, and that quitting Trek had been the cure.

You have deeply misrepresented who I am in your book; you have no idea who I am, what my work is, or what I did for TREK. I was deeply hurt by Gene and his lawyer. Promises were made and broken. After seven years of silence, I spoke to Joel Engel because I wanted the truth told at least once. Part of what I told Engel was favorable to Gene. Part was not. That was Gene. Warts and all.

Frankly, I am tired of after-the-fact explainers adding additional bullsh!t to the pile. Gene spoke out regularly about how I had betrayed him. He did this at one convention after another. Friends sent me tapes and clippings. I filed them and tried to get on with life. His speeches were reprinted in fanzines. He gave interviews to newspapers all over the world -- I have clippings from England and Australia where he railed on about me. Then the fans started repeating it. Now you. I have been saddled with a burden of lies by Star Trek's true believers, and your book is just another shovelful of the same old crap, and Joel Engel is the first reporter in seven years who bothered to call me up and ask, "Is this true? Do you have anything to say?" After seven years of calumny, abuse, and unofficial blacklisting, I do not feel I need to apologize for finally speaking up. Enough is enough. A responsible reporter would have checked his facts before printing them. You did not. You have not hurt me. You have hurt the credibility of your book, and your credibility as a biographer.

As I said before ... I have a life beyond Star Trek, and I have focused my attention where it belongs, on my writing and on my son.

My son and I have traveled all over the world together, we're a joyous family. I've been Guest of Honor at five conventions in the past twelve months, with two more to go this year. I had a novel published last November, another one just this May, and a new one scheduled for next June. I've had nine books published since I quit Trek. I have a story coming up in next month's F&SF. I just had a script aired on Babylon 5. I have my column in PC-Techniques. And I've done over a hundred thousand words of short stories for Resnick's anthologies in the past 18 months. I'm doing some of the best writing of my career since I've freed myself of the burden of the past.

Why do I tell you this?

Because I've been around long enough to know that what counts in science fiction is science fiction, not hype, not mythology, not lies.

Ten years from now, twenty years, whatever, I'll still be here writing science fiction, I'll still have the credential of my own work to speak for me. Whatever lies have been told or repeated, regardless of who has authorized them, I am confident that the body of my own work will stand as a suitable rebuttal to the steamroller of lies, and I can live with that final resolution. The readers will see for themselves.

Those who have made Star Trek a mythology, who have elevated Gene to Godhood, and who feel that the appropriate worship of the Great Bird involves the destruction of others have clearly missed the real point of Star Trek -- that we can only solve our problems when we learn to deal fairly with each other. This is the real tragedy of Gene's life -- that he himself never fully respected or trusted his own lifelong friends. This is what ultimately brought him the most sorrow. And this is the point that you missed in your book. What a pity. That would have been one helluva biography.

David Gerrold

------------------

Comments at TrekBBS